It will come as little surprise to most regular readers of these pages that a lot of guitar playing goes on in the Guitar Head office. Yes, we like to try out new equipment. Yes, we love to work out new and exciting materials for our books. And yes, we’ve got extremely tolerant neighbours in our building. But most of all we play for the same reason as our readers - we’re just crazy about guitar music!

It will therefore also come as little surprise to many of you that, whenever more than one of us is cheerfully strumming or picking away at the same time, the result is usually a blues jam of some kind. We’ve explored the importance of this genre at length over the past two years in this blog, discussing the history, artists, theory and techniques of probably the most pivotal style ever employed in guitar music. And our Blues 102 tutorial focused in particular on the 12-bar blues, that most legendary and enduring of chord progressions, responsible for shaping more songs and compositions than any other form in the history of popular music.

But how on earth can you make so many tunes using the exact same musical form sound so different? Well in lots of ways actually. Even if you discount the use of completely different styles (‘Folsom Prison Blues’ and ‘I Feel Good’ are both 12-bar blues, remember…) and stay purely inside the traditional blues arena, there’s thousands of different ways of organising lyrics, instrumentation, rhythm, harmony and other musical factors within that mere dozen measures of musical structure. And one that gives guitarists a particularly magnificent area in which to shine is what’s known as the Turnaround…

So what is a Blues Turnaround?

This is much easier to explain with a couple of graphic examples. Let’s first consider the basic layout of a typical 12-bar blues in E…

No real surprises here - a pretty standard harmonic pattern that all blues players will immediately recognise. But what could be happening over the top of that pattern?

It was actually the early spirituals which ultimately developed into the blues that helped to set one commonly used feature of 12-bar blues songs, namely the “call-and-response” layout of lyrics. A vocal “call” would typically occur over bars 1+2, repeat itself over bars 5+6, followed by a “response” in bars 9+10.

This clearly leaves three musical gaps, which can be perfectly filled with instrumental melody (such as a guitar riff!)

But here’s the important bit; whilst bars 3+4 and 7+8 simply stay on the root chord of our 12-bar blues, the final two bars act as preparation to jump straight back to the start. This musically climatic nugget of melody and harmony lifts us from the root to the dominant chord (an ‘imperfect cadence’ from I to V if we’re being technical), literally turning the tune around into another 12-bar section. Hence the name turnaround!

How to Play Blues Turnaround?

Putting this theory into practice is something that probably tens of thousands of musicians have achieved over the years – it’s no exaggeration to say that whole books could be written purely about blues turnarounds, and not JUST limited to the guitar either...

But let’s take a closer look at three ways you could approach this sonic challenge on your six-string, whether electric or acoustic.

-

#1: Ascending Chromatic Turnaround

This super-simple motif essentially makes your guitar assume the bass players role over the final two measures of the 12-bar pattern, walking up the low E string from the root through the major third, fourth, diminished fifth, and onto the fifth itself, culminating in a nice fat dominant 7th chord covering all six strings. Leadbelly, Robert Johnson, and other early blues pioneers frequently used this approach.

-

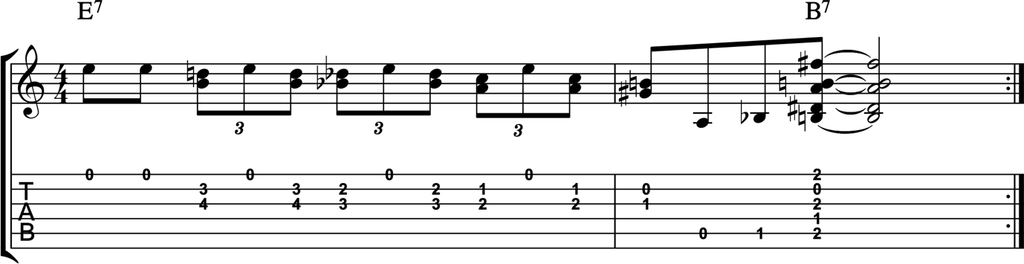

#2: Descending Chromatic Turnaround

Literally taking the opposite approach to our previous motif, we move down from our root open E on string one, dropping through the dominant 7th, major 6th, and minor 6th on string two until we hit the open B, but simultaneously picking a minor 3rd below on string three to make things a little more interesting. Polishing the whole thing off with one brief final walk on the A string up to a simple B7 chord, much in the style of Eric Clapton!

-

#3: Pentatonic Riff Turnaround

Stevie Ray Vaughan is our inspiration for this final riff, although we’d suggest using lighter strings than he did (15 gauge if rumour is to be believed – ouch!) Open strings, bends, hammer-ons and pull-offs are all involved in this deceptively complicated-looking blues-scale noodle – but it’s no-where near as tricky to carry off as it either looks or sounds...

Wrapping it up

And there you have it – history, theory, and practical playing advice, hopefully giving a great simple introduction to how you can approach your own blues turnarounds. The wonderful thing here is that you don’t even need anyone to jam along with; simply strum and sing over the call and response sections, then throw your own ideas over the instrumental parts. Meaning that, when you eventually DO try these tricks with other musicians, genius-sounding turnarounds should just fall out of your fingers with ease!

2 comments